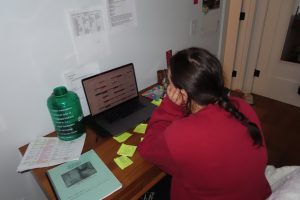

With her academic schedule pulled up in one tab and a notice of a therapy appointment in the next, sophomore Renee Moore’s computer screen symbolizes the current archetype of many college students.

Stress automatically defines college students, but you can take that to the nth degree during a pandemic.

“I could feel myself stressed about the amount of stress I was going to be under,” said Moore, a strategic and corporate communications major.

The increasingly competitive and rigorous world of Chapman often forgets that notebooks and laptops are not the only things students carry on their back everyday.

Mental health carries the biggest weight.

According to a recent report by the American Psychological Association (APA), college students belong to the age category found to contain the highest level of stress and reported mental health concerns.

Although mental health problems can be invisible by nature, some claim it to be what weighs undergrads down the most when academic achievement is given a higher priority.

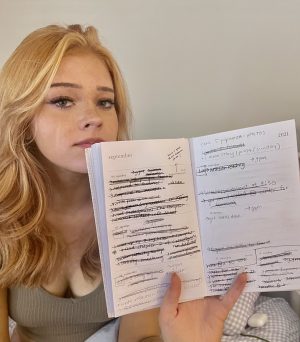

With the APA report concluding academic pressure to be 87% of college students’ most significant source of stress, junior Leven Edgar reflects on how this statistic is her reality.

“Sometimes I just stare at my to-do list and cry,” said Edgar, a screen acting major at Dodge.

A slew of papers, readings, homework assignments and quizzes make up an average weekly workload for each class in college. With most students taking over three classes, this load becomes multiplied on an incredibly daunting level.

In response to the alarming reported rates of stress amongst college students, Chapman psychology professor Chia-Hsin Cheng believes that an “increase in academic rigor and the added stress of navigating through the pandemic” has served as contributing factors.

“More than ever, students have to balance multiple roles and responsibilities while in college. School, work, and family,” said Cheng.

The outcome of such high levels of stress? Sophomore Dori Hasselbach would say: “mental and physical decay.”

“There would be weeks where I would barely eat or sleep because I was so stressed about school. I would be so worn down physically and mentally sometimes,” said Hasselbach, a communications major.

Physical health and mental health are known to be attached at the hip. When one spirals down, the other is bound to follow suit.

In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as: “A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

“There is no health without mental health,” said Dr. Brock Chisholm, first Director-General of WHO.

Obviously, there is little room to argue with the World Health Organization, but is mental health still given the same attention and care as physical health?

This seems to be the million dollar question.

Strict COVID-19 protocols on campus make coming to class with a cough even seem like a crime. To prevent the spread of the virus, the university has taken several steps to ensure students showcasing Covid symptoms are given accommodations.

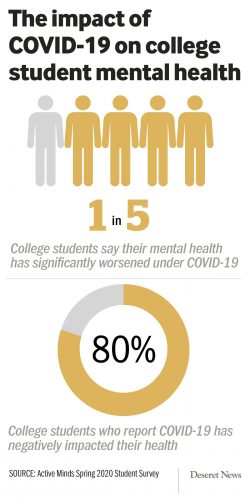

However, whether or not a student is wearing their mask above the nose should not be the only pandemic related concern professors have for students, according to the data graphic below.

According to a 2020 Active Mind survey of over 2,105 students, 80% reported negative mental health side effects based on the pandemic.

Worsening this data is the fact that suicide is the leading cause of death by college students.

These statistical rates reflect a need for universities to work just as hard on preventing the spread of the mental side effects of COVID-19 as they do with the actual virus itself.

In terms of academic leniency professors are willing to give for physical illness, Cheng believes “mental health issues should absolutely be given the same validation.”

“Depression and anxiety in particular, are top impediments to academic performance,” said Cheng.

Covid aside, mental rates among students have always been an issue concerning universities.

The Chapman Student Psychological center does offer mental health resources for students. However, junior Georgia Conlin doesn’t believe this fully bridges mental health and academics.

“I know I can book an appointment to talk about my problems, but there is still no easy way of emailing a professor to say ‘Hey I’m having an anxiety attack and your class is the main reason why, I can’t get your paper in on time,’” said Conlin.

In response, English professor Kent Lehnof wants to help his students succeed and said “granting an extension is certainly not that big of a problem.”

However, Lehnof believes that when it comes to this, faculty are put in a dilemma in terms of equity and fairness when students reach out to them individually.

“Do you just give an extension to anyone who asks? Is that then fair to other students who don’t ask? We just don’t have the same type of clarity when it comes from a student directly,” said Lehnof.

Meanwhile, Cheng believes this can be addressed by increasing mental health awareness on campus.

“There should be more mental health training for the entire college community including faculty, staff, and students. We should also improve screening and evaluation services,” said Cheng.

At the end of the day, while Moore believes universities and professors should continue to be more “mindful of mental health” on campus, she also believes it’s up to the students to “speak up and get the ball rolling.”

She adds: “Life is hard. School is hard. Learning how to be an adult is hard. Everything about this chapter in our lives is hard.”

However, Moore notes that “suffering in silence” is the hardest part of it all:

“Going to therapy changed the way I prioritize academics. The grade you get on that one chemistry test won’t hurt you in the long run. But neglecting your physical and mental wellbeing because of it might.”

Macy Meinhardt is a junior studying journalism at Chapman University. From a very young age, Macy fell in love with the art of expression and storytelling through dance and music, which eventually illuminated her path in writing.

Macy Meinhardt is a junior studying journalism at Chapman University. From a very young age, Macy fell in love with the art of expression and storytelling through dance and music, which eventually illuminated her path in writing.