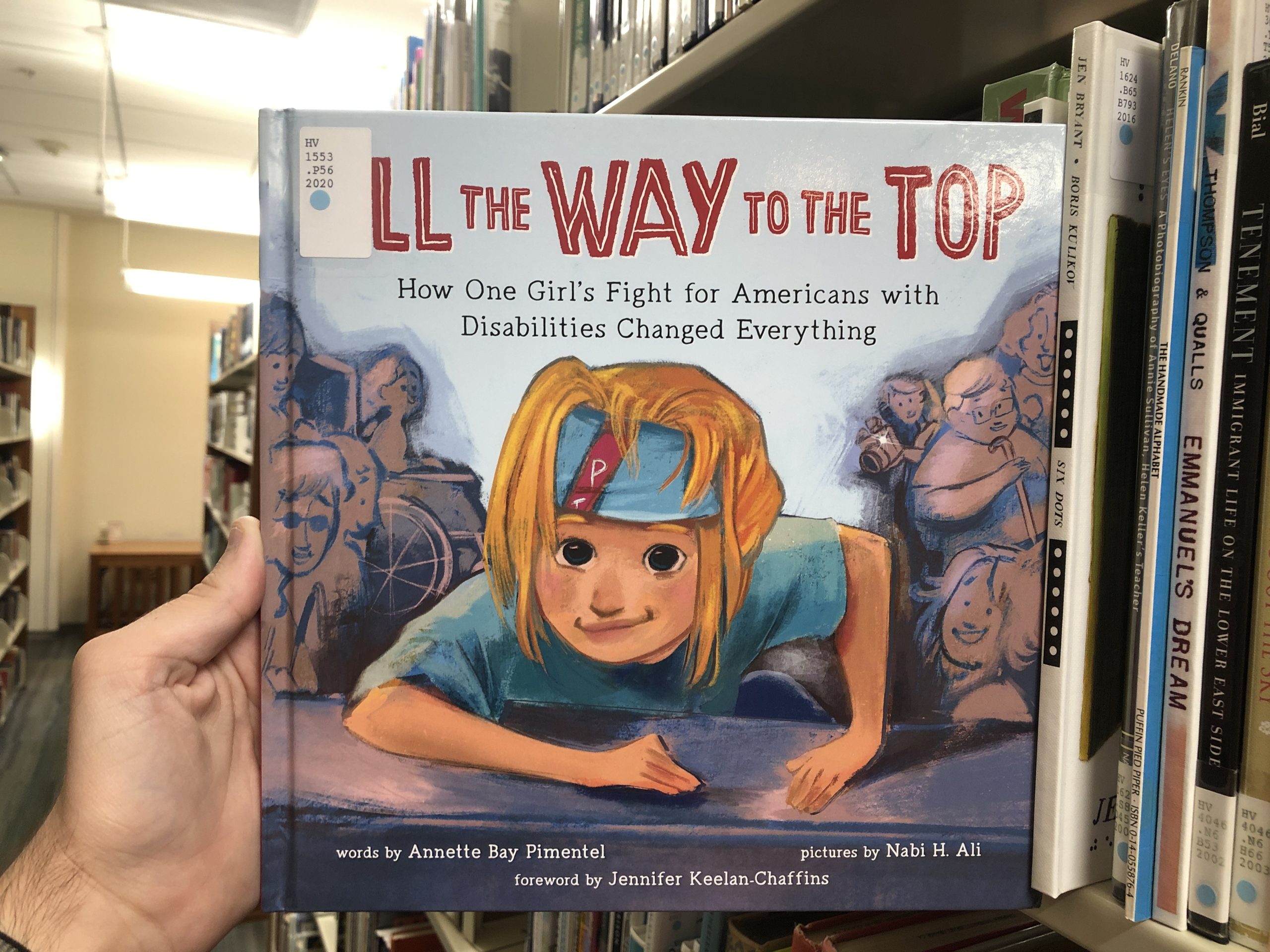

Recently sophomore Janie Batterton, who has an autoimmune disease, saw that Leatherby Libraries didn’t carry any children’s books that focused on characters with disabilities. Not on her watch.

After finding a children’s book on the subject, she offered it to Chapman. To her delight, the school bought the book and placed it in the library. She later donated another copy to the Kathleen Muth Reading Center.

“Yay!” she thought. “Finally, disabled representation in children’s literature.”

However, it’s but a small victory for Chapman’s disabled community, who demand more than pretty covers.

Students and staff with multiple disabilities – from hearing to chronic illnesses – have expressed complaints, feeling underrepresented in Chapman’s efforts for inclusion and diversity. While the school does provide support services for its community, some believe there should be changes on campus such as mandatory disability training for staff, an expanded curriculum and more effort to understand those whose disabilities are not apparent on the surface.

These disabilities, which can include dyslexia, diabetes, psychological diagnoses and so on, are typically ‘invisible,’ according to Jason McAlexander, director of the Disability Services at Chapman.

“If you see a wheelchair user, that’s a visible disability; somebody with Crohn’s disease is an invisible disability,” McAlexander said.

He explained that students with invisible disabilities can be accommodated, but, students and staff may not as easily understand their needs as those with visible disabilities.

“The administration is aware of it; the administration is not ignorant of students with invisible disabilities,” he said. “It’s just there’s a lot of needs for individuals with disabilities, and they vary so much, so it’s just hard to satisfy everybody.”

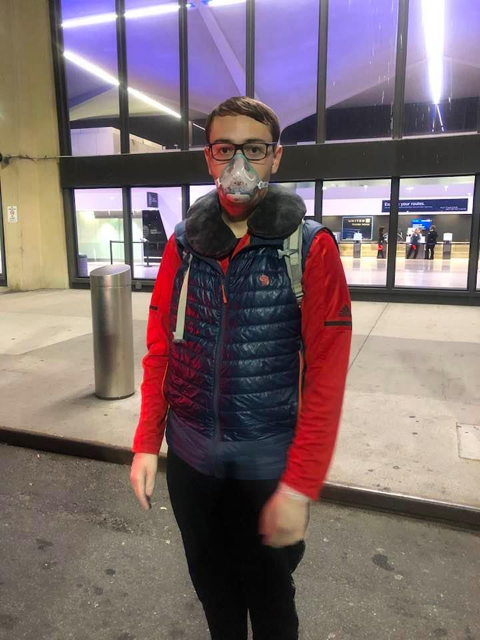

Some such students feel at risk in a post-pandemic world. One student who is immunocompromised, requesting anonymity, submitted six work requests between August 2021 and January 2022 asking facilities to fix her dishwasher. She asked them, as well, to let her know ahead of time when they’d be coming so she could ensure everyone was wearing a mask.

“I live in a private unit. I’m immunocompromised. I don’t give a shit who you are; you are wearing a mask when you enter my room,” the student said.

Bad news, as facilities did not respond to the student’s work requests. The student asked Residence Life, who got hold of facilities management. By the time this happened, Chapman had removed requirements for masks while indoors, so facilities entered the student’s room unannounced and maskless.

The student reached out to Residence Life after the incident, who explained masks were optional at that point and that they would explain the student’s concerns with facilities management.

“I understand it’s a Chapman facility, but I’m the only person that lives in there, and I’m the only person that has to deal with that person who comes in, whether or not they have COVID,” the student said. “It could be a cold, I don’t care; it still puts me at risk and I’m not okay with that.”

For some faculty members at Chapman, the relaxed mandate has been a blessing.

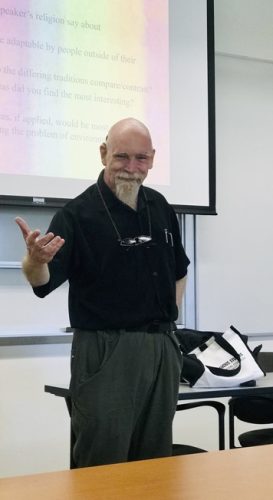

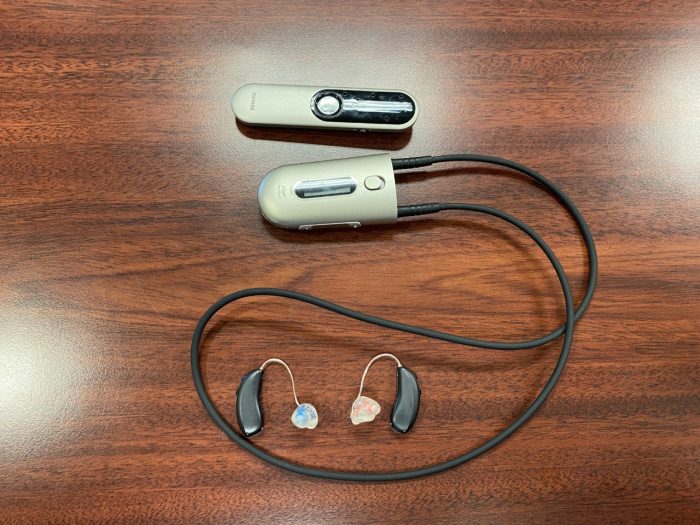

Lorin Geitner, a religious studies professor, is deaf without his listening device, and prefers teaching in person so he can better understand his students. For the first month or so of in-person classes, he had to persuade his students to wear transparent masks or transparent face shields so he could read their lips.

“Students need to know that if they have a disabled instructor, they should be willing to make at least minimal accommodations to enable the instructor to engage with them,” Geitner said.

Staff and faculty with disabilities must request accommodations from Human Resources, who assess their needs on an individual basis. Students with disabilities can request classroom accommodations, such as extended testing time or a note-taker, from Chapman’s Disability Services by submitting documentation to verify their eligibility.

The process isn’t easy for everyone. Brittney Staffieri, an adjunct professor teaching ASL 201, says some of her students with disabilities experienced difficulty in acquiring documentation.

“Many students have had to discuss their accommodations in private, and I educated myself on their needs so I can become more aware,” Staffieri said.

Staffieri, who is deaf, believes Chapman could do more to promote inclusivity for its deaf and disabled community. That includes hosting performances for deaf talent, classes on Black deaf studies and other courses that address the intersection of race and disability.

“As a deaf woman of color, I initially felt proud to represent a community that is often not represented,” Staffieri said. “There is some resistance, and it alarms me.”

According to Data USA, the enrolled student population at Chapman is 47% White, compared to 1.9% Black or African American. While disabled people are the largest minority group in the country, with 54 million Americans having at least one disability, Staffieri believes the needs of those with invisible disabilities are often ignored.

There are services at Chapman for students to better understand deaf people, such as the student-run ASL club. Chapman’s ASL program, however, will be discontinued next academic year due to a lack of resources and the recent resignation of ASL professor Rita Tamer, according to John Boitano, head of the World Languages Department.

He said the language department worked with the advising center and the registrar to identify similar ASL courses at schools in the local area.

“A student can fulfill the language requirement with ASL, but as of this spring, this is the last semester that we will be offering it,” he said.

Even students who have moved on from Chapman were surprised by this news.

“This must be a joke,” said Cianna Platt, a Chapman alumna who experienced hearing loss near the beginning of the pandemic.

While Platt stopped taking ASL classes before losing her hearing, she said she greatly benefited from the program later on, which led to her being more involved in the deaf community.

“Unfortunately, my ASL is really rusty, but I know enough to interact and enjoy myself,” she said.

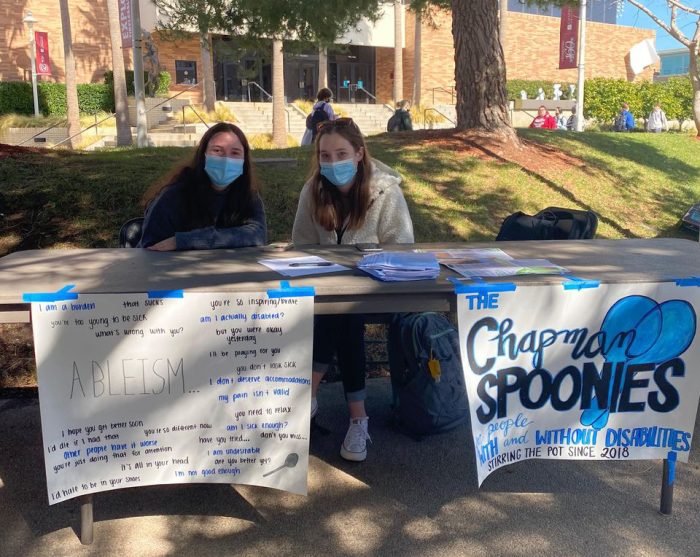

It’s not only students with hearing disabilities who are voicing their opinions. Kristin Kumagawa, the advocacy and activism representative of The Spoonies, has systemic lupus erythematosus, a common form of lupus. She values her time at Chapman, but hopes the school will listen to and understand those whose disabilities are non-apparent.

“Personally, I do love Chapman; I have so many frustrations with it, but, overall, I’m very grateful for what I have been able to accomplish here,” Kumagawa said in a joint interview with Linley Munson of The Panther Newspaper. “But there are so many ways that things could be improved if they took the time to listen to their community.”

For Kumagawa and other members of The Spoonies, listening to students involves requiring disability training for professors and new hirees, reviewing the university’s accommodation policies, and pushing for more representation for people with disabilities in classes and a different attitude with regards to language.

Director McAlexander explained that disability services do offer training to faculty, but acknowledged that they could provide more, if needed. “It’s just an ongoing thing of training and awareness that we just need to keep pushing.”

Batterton, the social media manager for The Spoonies, is working on a project regarding language surrounding disabilities after hearing professors use derogatory terms, such as ‘differently abled.’

“We wanted to make it clear that saying ‘disabled’ is not a bad word,” Batterton said. “It is not a taboo subject anymore; we want you to talk about it and discuss it.”

Batterton hopes that the initiative, which started as a class presentation, will inform not just Chapman faculty but students as well.

Overall, Chapman’s disabled community hopes their needs are understood.

As Staffieri said:

“Disability is a social construct, and the fact that the world around us is inaccessible makes us disabled, not the condition itself.”

Nolan Thompson is a senior majoring in film studies and minoring in visual journalism. When he isn’t writing, he enjoys going to the movies, taking photos and kayaking.

Nolan Thompson is a senior majoring in film studies and minoring in visual journalism. When he isn't writing, he enjoys going to the movies, taking photos and kayaking.