Everyday the deaf community struggles with living in a hearing-based society.

Increase that tenfold and you have what it is like to live as a deaf person during a global pandemic: chaos.

“Literal barriers are being created for our deaf and hard of hearing neighbors (or DHH),” said the Orange County Health Care Agency in a pandemic video.

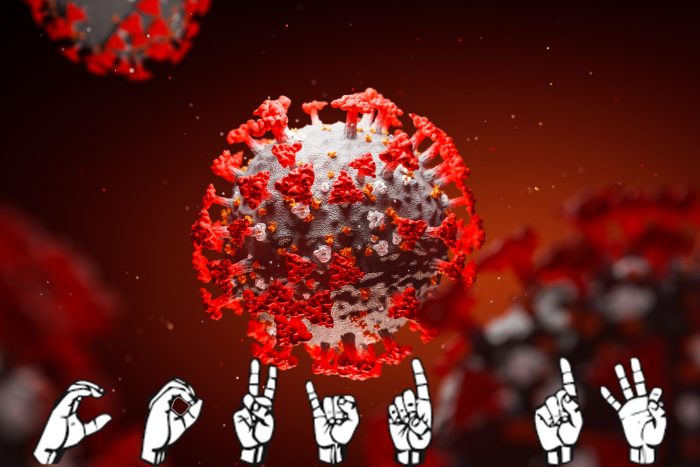

Wearing face-coverings and social distancing is essential to help slow the spread of COVID-19, however, this is inhibiting a major part of American Sign Language: facial expressions. Facial expressions are paramount in communicating with the deaf community, it is a part of the grammar of the language.

For example, in English, if you were to read an essay without any grammar, it would be very difficult and hard to understand. With the deaf community, however, everytime they walk outside and interact with the community, they have to put in monumental effort to understand people.

And that doesn’t even include the strain of communicating with people who aren’t willing to work with them.

“DHH community members are finding it extremely difficult to interact, convey, and most importantly, understand the world around them,” said Orange County Health Care Agency.

Almost 500 million people worldwide have disabling hearing loss.

When news first broke out about COVID-19 in the United States, the deaf and hard of hearing community were not receiving the information they needed. Most news was being spread verbally, with no interpreters in sight.

YouTube had an onslaught of creators that knew American Sign Language (ASL), reporting the news for the community.

But it was not mainstream. Many of those in the deaf community were at a disadvantage of what to do.

For many of those in the deaf community, English is not their first language, it’s sign language.

Professor at Chapman University in the World Languages Department, Rita Tamer is a polyglot, fluent in seven languages: English, American Sign Language, Armenian, Egyptian/Arabic, French, Italian, and Spanish. She even began creating a new language: Armenian Sign Language.

She has repeatedly emphasized the need for accessibility for the deaf community in a hearing world. Due to the sudden outbreak of COVID-19, there has been delayed information, misinformation, and misunderstandings given to the deaf community. Sometimes due to their education, deaf people can have a reading level of 6th to 8th grade.

“The deaf community is constantly struggling, they are not given the attention they need for accessibility,” said Tamer.

American Sign Language is HEAVILY reliant on facial communications and expressions.

Both of which are obscured by the mask.

Tamer notes said that there have been a small group of people who have created masks with a clear covering for lip reading and expressions, however, it gets fogged up everytime you breathe, once again obscuring the face.

“[Clear masks] are better than nothing, however, many deaf people may not respond if they cannot see your lips moving, creating a misunderstanding because of the mask,” said Tamer.

Linnea O’Donnell is a junior television and writing major at Chapman and is currently taking ASL 201. She began to get interested in deaf culture when her elementary school had a deaf-ed program as well as her mom being an interpreter at a very basic level.

O’Donnell has spent a lot of time studying deaf culture and the proper ways the hearing should communicate with the deaf.

“Be willing to educate yourself and learn some basic signs. Be willing and open to have that communication, rather than you need to communicate with me,” said O’Donnell.

O’Donnell worked briefly at Chipotle during the pandemic and saw some of the stark communication issues that occur with the deaf community. There were handfuls of people who were deaf and would come to get food and had to communicate with Chipotle workers.

“My coworkers got a little standoffish and uncomfortable with people who are deaf and it was disheartening and disappointing to see,” said O’Donnell, “You can communicate with a person with any hearing status. It is just bias.”

Tamer and O’Donnell both say that the hearing community helping the deaf community integrate into mainstream society without feeling isolated and discriminated against, is the goal.

People expect so much out of the deaf community. They are expected to lip read and speak with little effort in order to be treated with respect.

Tamer points out that being deaf is a part of their identity, not a disability. And denying them information and access to what hearing people are able to receive during a global pandemic is just a small example of this bias.

People need to put themselves in others shoes, and like Professor Tamer said,“You don’t know what you have until it’s gone.”

However, the Orange County Health Care Agency emphasizes that there are still ways we can all help:

“We can use hand gestures to bridge the gap or use clear face shields to help the DHH community read body language and facial expressions. Phone apps can be used to create visual notes and the use of personal writing devices, like Dry Erase Boards, help lower the risk of catching or spreading the virus.”