While social movements like the Women’s March, It’s On Us and TimesUp are in a full sprint to gender equality, the Greek system is dragging its feet.

“It’s not Greek life that’s the issue, it’s societal, “ said Lauren Paul, who served on her sorority’s policy and standards board. “If you saw a man chugging a beer [on social media], it’s whatever, but if girls are doing that, it’s trashy.”

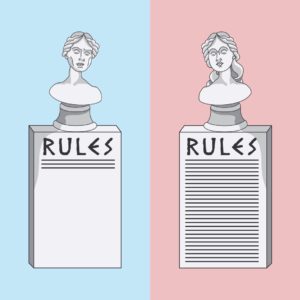

Social movements across the country are encouraging young women to strive for equality, yet the college Greek system maintains a unique binary system: sorority women implement numerous rules and are expected to obey them, while their fraternity counterparts choose to rely on a more informal system. While it is difficult to generalize anything in Greek life, the system we know today is the product of hundreds of years in the making. Each chapter has a different set of guidelines, relationship with its national office and approach to accountability, yet there are still objective differences between men and women’s social flexibility.

“(Sororities) have to hold ourselves to a higher standard because if we screw up, they’ll have more reason to shut us down,” Paul, a junior strategic and corporate communications major, said.

National Panhellenic Conference (NPC), the organization that governs sororities nationwide, has a 191-page manual detailing the suggested structure for all female Greek chapters. Meanwhile, The North-American Interfraternity Conference (IFC), the equivalent group for men, has a 16-page constitution.

Chapman Greek life has a principal role in campus culture. Without popular sporting events to mobilize students, it seems to fill the void of campus camaraderie with events like Airbands, Skit and Greek Week. There are 16 social chapters on campus, and one third of students are involved in a Greek organization – higher than the national average of 10 percent, according to a report by Student Poll.

Greek life found its roots in academics; the first student secret societies were formed in the late 1700s to discuss topics like politics and philosophy outside the classroom. It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that social fraternities gained their footing, and they started to establish chapters on multiple campuses. After which, female organizations began forming, according to Rehoboth Journal.

The annual National Panhellenic Conference was first held in 1902, to discuss the “restrictive social customs, unequal status under the law and the underlying presumption that (women) were less able than men,” according to the NPC.

Culturally, fraternity men are celebrated for throwing parties and post photos hoisting handles of liquor. The public perception of frat culture can be seen in Hollywood; Animal House, Old School and Neighbors are just a few of the movies which depict the “brotherly lifestyle.”

Despite fraternity stereotypes, statistics tend to support the idea that they enhance a young man’s ability to succeed – even without the structure that sororities employ. Of the nation’s 50 largest corporations, 43 are led by fraternity men. 76 percent of all Congressmen and Senators belong to a fraternity and dozens of United States Presidents were affiliated.

Yet in the last 150 years of American Greek life, there have been roughly 130 hazing deaths, five of which were sorority women. Two of 2017’s hazing deaths were in fraternities that Chapman has on campus: Beta Theta Pi and Phi Delta Theta.

This is why, sorority leaders explain, women implement so many rules.

“It’s all preventative; it does kind of stink, but it’s to make sure that we are being safe,” Paul said.

One of the most tangible differences is the structure for Greek formals, which are social events chapters host – almost like a college version of prom. Greek men host weekend-long formals in party meccas like Las Vegas, Palm Springs and Lake Havasu, while women have formals that last no more than a few hours, and where bussing is required to prevent impaired driving.

Then there’s the point system, which most sororities implement to keep women involved in their chapter.

“If guys tried that structure, it would fall apart,” junior news and documentary major Tristan Davis said, who is currently serving as Chapman’s Interfraternity Council president.

Missing mandatory events such as initiation, chapter meetings and recruitment can result in membership fines, which women must pay in addition to monthly dues.

Former Chapman fraternity president Matthew Goldstein said when presented with the point system, his fraternity’s executive board vetoed it.

The junior business major accredits these differences to men’s overall attitude toward rules.

“As a guy, Greek life or not, we don’t take being told what to do very well,” Goldstein said.

When it comes to academic performance, Chapman’s sororities excel compared to the fraternities. At the national level, fraternity men on average

have lower GPAs than non affiliated students, according to a 2016 study by the Social Science Research Network.

This is something Dean of Students Jerry Price said he is concerned about. Greek life is social by nature, but sororities tend to be more academically inclined than fraternities.

“Most sororities are able to show you a portfolio that they do pretty well grades wise, but I’m wondering if we need to start coming up with a report card for particular fraternities to say they’re delivering on scholarship,” Price said.

Senior John Ryder has served on his fraternity’s executive board and as IFC president said his chapter’s focus on scholarship as delayed. The broadcast journalism major said it took until the latter half of his time at Chapman for his chapter to incentivize academic achievement at all.

“With fraternities, it’s a little more hands-off,” he said.

According to Chapman’s Spring of 2017 Greek Grade Report, 45 percent of sorority women had a cumulative GPA of 3.5 or above while only 22 percent of fraternity men met this mark.

In addition, Chapman sorority women tiptoe to avoid social scenes that could be misconstrued as hazing, and are often told to ignore pledges at parties to avoid risk. Chapman fraternity men, by comparison, openly throw parties for their pledges where binge drinking is the norm.

“I never go to kickbacks with anyone in my sorority because I’m trying to abide by the rules. When I do run into my sisters at fraternity parties I feel really ashamed. I feel like daily actions are obstructed by the rules,” Madeline said.

One would assume that perhaps the reason fraternities are much more relaxed is because they have different bylaws, and this part is true, but when it comes to safety and liability, fraternities and sororities actually fall under the same insurance policy: the Fraternal Information and Programming Group (FIPG).

This policy is the leading risk management guideline for all Greek chapters, female or male, yet when it comes to organizing events under this umbrella policy, fraternities are simply more willing to take risks with their insurance than sororities, according to Chapman’s Greek Life Coordinator Jaclyn Dreschler. This means that sororities do not grant themselves the social freedom that fraternities enjoy, despite having the insurance.

Fortunately, Chapman has not had any large-scale Greek scandals that recount hazing deaths and serial assaults, but there is a fair share of scandal. There have been rumors of strippers at fraternity houses and hazing rituals, and this semester one man suffered a drug-related injury at a formal and had to life flighted from Big Bear.

In Spring 2016, former Delta Tau Delta Vice President of Finance Austin Kernan was caught embezzling money from his fraternity – shortly after being elected SGA president.

This isn’t to say that women don’t commit infractions, but the types of violations vary greatly. While men tend to get in trouble for parties and safety, women tend to hyper-focus on rules regarding recruitment, reputation and social media violations.

“On the sorority side, after working in the Greek office, I’ve noticed that there is a lot of cyberbullying and social media problems,” said Ryder. This observation stems from the reality that sorority women create social media regulations to prevent harsh judgment of their organization.

Women choose to run their sororities this way, and men opt to utilize an informal system. The chapters’ national offices create and perpetuate this system, but some students said they understand the reasoning behind this.

“Panhellenic has a lot more rules. It tries to create a more constructive environment than IFC,” said Alex Freres, a junior business major who is president of her sorority.

“Fraternities like their lack of structure, they like to bond with their brothers and not have anyone have to coordinate the logistical side… the women who want to join our organizations are very empowered women who aren’t afraid to have structure,” said Madi Murphy, a junior strategic and corporate communications and political science major who is the President of Chapman’s Panhellenic Council.

Dreschler explained that the majority of Greek regulation comes from an individual chapter’s national office. The school tends to intervene only if the Student Code of Conduct is broken, and Chapman’s IFC and Panhellenic exist to foster a chapter’s pre existing structure.

This means that the closer the relationship to a chapter’s national office, the tighter the structure will be. Dreschler said this connection tends to be stronger with sororities.

Looking toward the future, perhaps sororities and fraternities could aim to learn from each other. National IFC has already taken a step toward a more structured future with the recent employment of IFC 2.0 – a fraternity redesign with the goal of structuring a safer environment for college men. Sorority women nationwide may also be undergoing a shift in identity – with recruitment increasing by 50% in the last ten years, particularly in the Ivy system, a sorority reformation may be underway.

But it may take years for the effects of this shift to be fully realized at Chapman.

“As many rules that you can put in x-number of documents doesn’t mean anything unless behavior actually changes,” Dreschler said.

Despite the disparities associated with Greek life, Chapman students continue to wear their lettered sweatshirts with pride. Greek life, so it seems, is only growing in popularity at Chapman, with a new fraternity, Delta Sigma Phi, being introduced to campus this semester.

As young people join and often lead fervent discussions about social change in communities and the workforce, one question about our own community becomes ever-relevant: how does Greek life reinforce antiquated gender norms?