Come this May, Chapman University will have completed its first year of the new Strategic Plan for Diversity and Inclusion. But is the campus any more diverse – or inclusive – than before the plan began?

That’s hard to say.

The Strategic Plan for Diversity and Inclusion began a year after Daniele Struppa became president of Chapman in 2017, with a five-year timeline and many goals. Those goals, though, are indefinite at best. On the page describing the plan, a specific list of objectives is not shown.

The Snapshot, where more goal-oriented language is used, speaks of faculty workshops and surveys with overwhelmingly positive responses, but those surveys have questions like “Chapman is an institution that values diversity.” Nothing in the plan outlines hard numbers.

Chapman has a median family income of $149,800 and is 53.2 percent white, according to an analysis by the New York Times. Anecdotal evidence on college informative forums shows that the campus reputation of being mainly white persists into the general public’s view of Chapman. Some Chapman officials are hoping that the Strategic Plan will change all that.

The Diversity Project is “focused on developing strategic priorities and recommendations for diversity and inclusion at Chapman,” according to Chapman’s website. The Year One Snapshot paints a picture of successful initiatives and new hires, like those of the directors of Jewish and Muslim life, to increase on-campus and surrounding diversity and awareness. The Snapshot also points out several concrete achievements including the addition of a new minor in Latinx and Latin American Studies and a hefty increase in the budget for the Cross-Cultural Center.

But the first year of the project has also featured stumbles, many dealing with the president losing his footing in regard to black students.

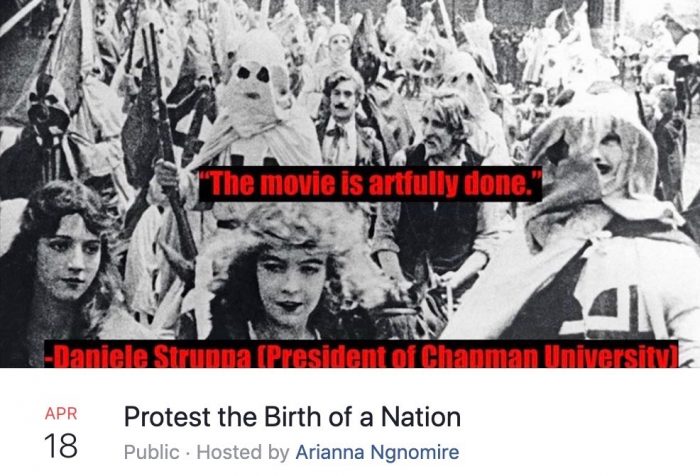

On April 18, over 100 students gathered in objection to two posters advertising The Birth of a Nation, a 1915 film praising slavery, hanging in the halls of the university’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts. The posters were subsequently taken down, but not before Struppa released an editorial about his experience watching the film.

“The article [Struppa] wrote about The Birth of a Nation poster in which he stated that he should be commended for watching the film in the first place? Problematic,” said Kyla Stone, a junior theatre performance major.

Struppa wrote an editorial defending his decision to let the poster remain in the Dodge hallway, sparking unrest within the student body.

“It sparked so many different opinions on students’ rights at Chapman,” Stone said.

Struppa ultimately relented and said he would allow faculty to vote on taking down the poster, stating that simply taking it down would be “censorship.” Though the faculty voted to remove the poster, some say that the protest and the vote should not have had to take place at all.

“Why am I educating the president of my university, who has more degrees, before I have even gotten mine?” Naidine Conde, the current president of Chapman’s BSU, asked at a forum discussing the poster, according to an article in The Panther.

“Really, the protest was just a megaphone to issues that had started years ago. I know that my first year, the BSU was talking about it and there were complaints formally written in an email about it,” Arianna Ngnomire, a senior screen acting major said.

“I feel there is a responsibility that our university has got to acknowledge more often: that our voice as students truly matters and that it should be taken seriously,” Stone said.

The uproar surrounding the posters is not the first time some feel Struppa has misstepped. In an interview with Chapman Prowl, Struppa said that the African-American population is only “about one percent in Orange County, so I don’t expect to see the numbers to grow much more.”

That statement put Struppa’s sincerity about bolstering diversity in question for some.

“I don’t think that should be your aim, necessarily,” said Ruben Espinoza, assistant professor of sociology and Faculty Co-Chair of the Community Task Force.

“Maybe in Orange County it’s two percent of the population that might be identifying as black or African American,” Espinoza added. “But it’s not just California students or Orange County students that are coming to Chapman.”

Ngnomire shared a lack of understanding as to why Struppa would settle for matching the surrounding demographic. “I just don’t know if he’s trying to improve community relations with Orange County, but it doesn’t seem strategically sound,” she said.

Regardless of the numbers of the surrounding community, though, colleges are institutions that people come to from around the globe. Chapman itself has current students from “49 states, two U.S. territories and more than 80 countries, including Canada, China, France, India, Japan, Mexico, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and the United Kingdom,” according to the university’s International Undergraduate Admissions page. Many of those places have a black population greater than Orange’s 2.1 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“When you look at the numbers in terms of race, it’s hard to label Chapman as what I consider to be diverse, especially in terms of who is represented in your classes,” Stone said.

“There’s the issue of recruitment and retention. You know, our African-American population is really quite low, where in the past it’s been much higher than it’s been at the moment. We had a larger population of Middle Eastern students at one time,” said Mildred Lewis, a professor in the English department at Chapman.

The on-campus resources and support for students of color need to be improved greatly, according to Ngnomire, who was the 2018-19 Student Government Association vice president. “That needs to take place before recruiting more students of color in my opinion, because we’ll still run into a retention rate issue if we’re not creating community and belonging,” she added.

Many have turned to the Strategic Plan to make specific improvements. The initiative has five Task Forces: the Community, Curriculum, Communications and Perceptions, Demographics, and Physical Space Forces all cover a different aspect of the university experience.

However, Chapman’s website states that only two of the Task Forces have met during the 2018-2019 academic year: the Community Force met four times during the first semester, and the Curriculum Force has met every other Friday since September 7.

And the other three Forces have failed to meet at all.

“Sometimes it’s just busy schedules, sometimes it’s the lack of students in it,” said Jacky Dang, the Undergraduate Student Co-Chair of the Curriculum Task Force.

And one of the least represented groups at Chapman, poor people, may have lost their chance at representation entirely. Dang noted that a task force formerly known as the Socioeconomic Stratification Force had been struggling and was ultimately disbanded due to a complete lack of student involvement. Only 4.2 percent of Chapman students come from families from the bottom 20 percent of household income, according to the same New York Times analysis.

“But it’s for student needs, and so it was kind of, well, how do we know what students need if they are not able to make it?” Dang said.

The lack of involvement seems to be chalked up to a lack of student interest or knowledge. And, in fact, many students don’t even know this initiative is happening.

“I honestly haven’t noticed much,” Stone said. She went on to say that one place she had seen improvement was the theatre department, which houses multiple audition-based programs.

“The freshman class of theatre and screen acting majors seems to be more diverse in terms of background, which is both awesome and exciting,” she said.

“I wasn’t expecting to see huge changes in a year. I think that often diversity initiatives are asked to do too much too quickly in our understandable anxiety to see things move forward,” Lewis said. “In terms of my own expectations, I’m not satisfied with the progress it’s made ever, but I think the plan did and is doing what it should be.”

While some are worried that the initiative’s efforts are not far-reaching enough, there have been strides made over time.

Chapman has had a long history of problematic interactions with people of color who do not necessarily follow the mainstream. In a recent issue of Chapman Magazine, former student body president Rick Davis said he was threatened with expulsion if he followed through on his invitation of Angela Davis to speak at the university during the 1974-75 school year. Davis was a prominent political figure and author who was an outspoken member of the Black Panthers, and instead spoke at California State University, Fullerton.

Recently, though, Davis was the 2018 keynote speaker at the Western Regional Honors Conference held in Chapman’s Memorial Hall. And some people do feel comfortable in Chapman just the way it is right now, even some of those who are considered minorities.

“As somebody who went to predominantly white institutions, I feel really comfortable in terms of navigating Chapman,” Lewis said.

But that comfort is not experienced by everyone, and some still feel that their race creates division between them and the rest of campus life.

“Before coming to Chapman, I always had my mom to go back to, who’s black and from Cameroon, and so I was, even without trying, pretty strong in my black identity. At Chapman, I think I’ve had to learn a lot more,” Ngnomire said. “I see myself as a leader, as someone who is trying to teach others, if you’re black or not, about the black identity in the spectrum as a whole.”

“You know, as a professor, I think it’s a balancing act in terms of how much you share of yourself. I’m really here to help the students and to facilitate their growth, so I bring in my multiple identities where I feel they are relevant,” Lewis said.

So speaking on diversity in the classroom is definitely a tricky subject. And outside the classroom, it’s really no easier.

“Diversity initiatives can look a lot of different ways,” said Bobbie Porter, the Assistant Vice President of Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity at California State University, Fullerton.

CSUF, a public university only seven miles from Chapman and one-fourth the cost of its tuition, recently became one of only 96 institutions in the United States and Canada to receive the Higher Education Excellence in Diversity Award, which recognizes institutional commitment to improving and sustaining diversity.

To Struppa’s point about the Orange County population being 2.1 percent black, Fullerton thumbs its nose.

“We’re definitely a twice-over minority-serving institution. We also pride ourselves on being able to bring in students who wouldn’t traditionally access higher education,” Porter said. “We are a campus that truly is a space for diversity, and specifically how diversity looks in Southern California.”

In comparison? Chapman is still largely white and well-off.