Remembering Grandpa comes in bits and pieces. Rather than one specific occasion, I often am reminded of his tendencies and the trinkets he collected throughout the years.

Grandpa was defined by remotes, and baseball games that were somehow still playing on the boxy T.V. in his room long after he had started snoring. He was defined by his weirdly high tolerance for beer, and the suspicious, most likely expired lemon shaped candies he kept in a plastic bag, because he knew we’d be coming, and wanted to give us something. He was defined by his rare, but very powerful laugh. It was hard to get one out of him, but if you did, you felt like you had won the lottery. He was defined by knitted blankets, $2 bills, an endless supply of crewnecks, and black hair that persisted even when the rest had gone grey. Somehow his hair found a way to be as stubborn as he was.

Grandpa was defined by his deep distrust for most, if not all organic foods, by the empty spot in the garage that never should have been there because the DMV took his license away a long time ago, and by the fact that he thought it was funny that another car hit his, but they never asked for his license because he wasn’t the instigator.

In all honesty, I found my grandfather to be quite the enigma. In my younger years I had written him off as a play by the rules kind of person, but then he would shuffle home with a $500 television he won gambling at some casino, and my whole perception would get turned on its head. For all his stoicness, he was not above a good sardonic joke now and again. He had a particular fondness of calling my youngest sister Emme, “the boss,” and asking her to keep Lulu and me in line. This was a joke because I think we all know that I am the boss of our family, but I digress.

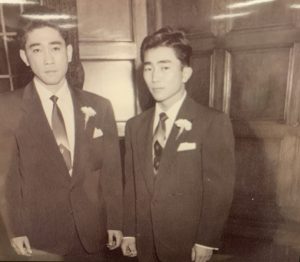

Grandpa also wasn’t the most open of people, but as he got older, he started to talk to me more about his past. Every so often, I’d catch whispers about Rohwer, and small stories of the Korean War. The Japanese internment and his subsequent conscription into the army were scars that never quite healed. Truly, I was never able to comprehend how this country had the audacity to ask him to serve after locking him away for years.

Once, after much prompting, he told me about this “broad” that sat on the hood of his car preventing him from driving away. She must’ve at least made a good impression, because a few movie dates and Frank Sinatra serenades later, they had been married for 67 years.

He liked to do that, put up a tough front when talking about the people he loved. He would scoff and banter to my Dad’s face, but then go and tell everyone that HIS son in law drove a Cadillac, and that was pretty cool. Rather than ask directly how college was, he would use his go to opener: “I don’t think they’re giving you enough homework,” and wait for me to bite before starting the conversation.

The heartbreak you feel from losing a loved one is unlike any other. The perceived permanence of it all hits me sometimes, and I find myself in a college dorm crying and gasping for air. I do find some solace, however, in seeing everything I saw in him in each and every one of my family members.

I see him in my cousins’ Mark and Scott’s ability to play poker. I see him in my Dad’s drive, and my Aunt Nancy’s spirit. I see him in my Mom’s ability to never forget a grudge. My Dad likes to say that’s a Fukuya thing. I see him in my sisters’ love for lemon candies, in Lucas and Calvin’s laughs, in Uncle Kim drinking a beer in the kitchen.

One day, I hope that people can see everything he was in me.

Ava McLean is an avid traveler, milk drinker, and artist. Her life’s biggest regret is bleaching and dying her hair with information she received off of Youtube. Her hair is still recovering from that experience.

Ava McLean is an avid traveler, milk drinker, and artist. Her life's biggest regret is bleaching and dying her hair with information she received off of Youtube. Her hair is still recovering from that experience.